Lee Kang-Wook

On Lee Kang-wook’s Painting – A Representation of Sensuous Illusions

By Yoo Jin-sang, Professor of Kaywon School of Art and Design & Art Critic

An atom is nothing but an assumption for our convenience. It does not exist in reality. What is present is nothing but an idiosyncratic feature in the same physical continuity. Atoms are the conceptualization of the spirit isolating matter from all attributes of beings. In fact, the spirit makes all beings remain in a complete, independent four-dimensional world. As if surrounded by a myriad of mirrors, what makes a reflection by these singular atoms is none other than a sensuous illusion. (Gaston de Pawlowski, Travel to a Four-dimensional Space, ed. Images Modernes, 1923, pp. 104-105)

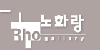

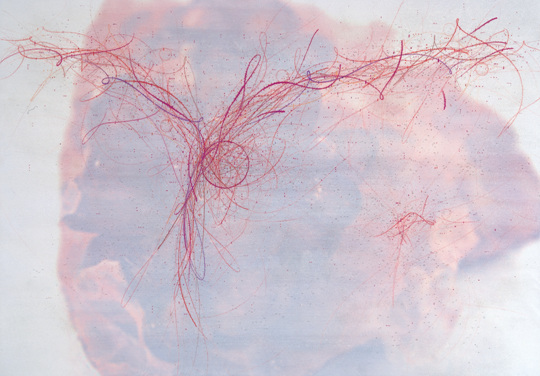

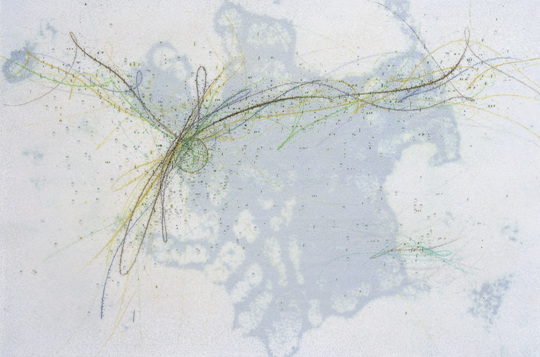

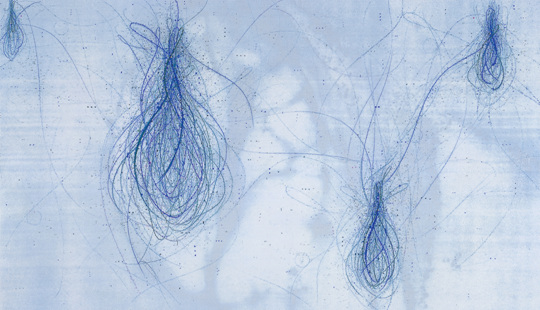

The rhythm of endlessly reiterated lines and innumerable dots spread near them, vigorous movements, unknown depth of space, dim stains and flickering lights — The world Lee Kang-wook’s painting represents is greatly different from what we see in daily life. This is an evocation of tremendously spacious space, namely a cosmic space and extremely restricted space, namely a place full of particles simultaneously. The images Lee captures seem to very delicately associate the beauty of such spaces through a conceptual, concrete indication. The composition of each element in his painting is an eloquent manifestation of aesthetic impression we expect to discover in both macro and micro spaces. At the same time, Lee’s painting is a repeated record of autonomous lines and dots. The lines, numerously rendered, disappeared, and re-emerged, make a painterly space the place where the plurality of body and gaze is produced. In this respect, a distinction between ideal and generative space become of no significance.

What does painting point out? Is that an illusion created through a blending of lines and colors? Or otherwise, is that a concrete content or his thought that he recorded through the composition? What Lee Kang-wook represents is the two, physical activity and ideal description. The moment when the features of images we face are most eloquently represented is not the state we have to select one of them. That is rather the moment when a painterly composition produces a new level of sensation and meaning. In painting, surprisingly, that becomes reality and illusion at the same time. In this sense, a painterly space as the place where potential images and events take place is presented as a metonymic substitute. An invisible space in his work Invisible Space refers to a place outside our visible world and simultaneously a painterly space that can be captured only by the power of the gaze.

According to Roland Barthes, what is finally consumed in capitalist society is the individuality of the body. In his writings on Cy Twombly, he said that nevertheless, the body transcends its exchange value. Any transactions and any political implications in the world cannot weaken its value. What is extreme here is the fact that the body is given without any rewards, he also argued. This allusion suggests a radical characteristic of drawing’s corporeality. What Lee’s painting produces is corporeality. Lee describes a space, determines grids and places logos in it, but simultaneously blots out it, ridding of time and space by the overlap of lines on it. When deleting the body, painting is a record of its trace. Although he depicts something, that has no purpose, no models, and no occasions. Drawing’s political quality is derived from its objectless writings. Inscription of an attitude, not representation, is the core.

Lee Kang-wook’s work is made up of a myriad of lines that look like a long stream flowing in a direction but occasionally delineate a circle, as if underlining something. What defines open or closed lines, curves, and inflections is an aggregation of tangents that change at a regular speed, namely whose changes are always constant. If the dots vertically away from each tangent at a regular distance come to have a focal point (identity), a circle is formed. If the focus blurs, stains emerge in a certain area. When lines spread, the curves generate dim stains and dispersed dots here and there, crossing a broad district. In Pli, Gilles Deleuze addressed it as a description of the subject created by curves. The lines of the universe infinitely and constantly produce the subject through their movements. Lee Kang-wook’s painting seems like the images featuring such cosmic lines. These curves remain tied or untied, appearing or disappearing inside and outside a certain space. The outside is an unknown place and the images as its part or as a section are a document of some accidents occurred in a specific place and time. His work looks like an image that captures an extreme moment of forming a focus, by means of ultra-rapid exposure. Lee’s work unveils the movements of the subtle through a record of extremely short temporal aspects. Painting as a temporal section of a continuum.

A photographic metaphor is often used as one of the most efficient methods to account for Lee’s work. The surface of his work, that seems created through an application of silver, is much closer to an object generating an optical reflection than an object done with paint. This surface is derived from the transparent beads spread over an entire canvas. Lee’s intension of emphasizing a visual depth through a reflection of such splendid canvas becomes clear by arrangements of dispersed dots. Lee Kang-wook makes use of a really complicated method in addressing the perspective. He applies drawings to the blurred blots of a background appropriated from biological images like cell photos, and then sprinkles beads on it. He exploits three ways to represent an image. Although its background image is associated with a tiniest object ironically, such ways bring about a physical depth, lending a very intense dynamism to his work. The particles of the beads are like star dusts or atoms that carry lights, and the elements of undulation swiftly moving by the lines of drawing.

An illusion Lee’s painting generates through a sensuous surface is reminiscent of the attributes of atoms that Gaston de Pawlowski described in the early 20th century, accounting for a four-dimensional world. According to Pawlowski, a four-dimensional space cannot be captured by our perception, but some of its continual aspects brings about changes in our visible world. It can be perceived only when our spirit grasps a consistent subject in a continuum of a series of illusions. It never reveals its true nature in sensuous illusions, but the only way we can perceive it is through them. According to quantum mechanics, the only way to perceive always accompanies with errors occurred by observers. In his pseudo-scientific studies, Pawlowski expounded our reality detached from the objective truth or purity. We can find sensuality and splendor, plus insights into the true nature of painting in his painting. This is why a methodological solution to a mutual indication between the two is somewhere in his work.

Painting shows the most efficient condensation of potential expressivity in a limited condition of creation. Lee’s tireless reiteration of lines can be seen as an attempt to discover such condensed, transcendent arrangements. At the same time, his lines are a manifestation of his thoughts. In fact, all activities leave their traces. A distinction between such activities and their effects is intended to prove the inevitability of correlations with all that exist in the world. If all remains consecutive, any incident will not take place. Any non-separability between cause and effect may exist only in an extremely pure structure, an atomic physicist, Jules Vuillemin said. Panting itself does not exist as a pure structure but paradoxically, it separates an incident from its continuum, to represent the moment of extreme purity. This separation is a way of putting the world into a frame after condensing it. In Lee’s work, the methodology of separation and section is to represent the world and explore its sensuality. In Lee’s painting this is an occasion to solve fundamentally given contradictions and proceed to a next-stage aesthetic solution.

However, to find out every relationship in his paintings is not the best way to appreciate them. Lee Kang-wook’s work appeals to our intelligence and sensations as well. Such elements as refinement, tranquility, dynamism, and elaborateness are prominent in his painting. If addicted to these sensuous attractions, we soon realize what his painting let us know, which arrangement, condensation, and connotation the artist relies on to embody it, and what the virtue he has to conceal is, instead of revealing it. Our appreciation of his work may be perfect, if we fully understand these aspects.