Song Myung-Jin

Green Home

Obverse Side of the World as a Way Out

Lee Sun-young (art critic)

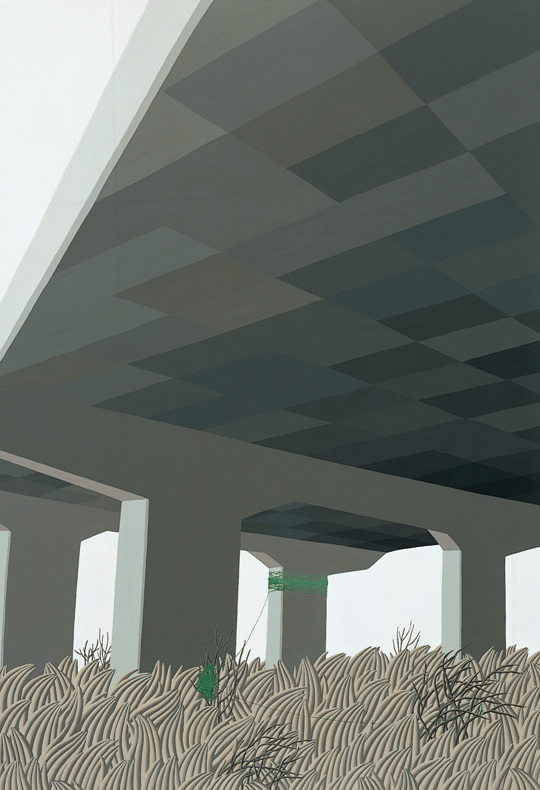

Beginning from the 2005 exhibition titled “Surface of Landscape”, there have been familiar motifs such as bridges, bushes and so on. Being representational yet unrealistic, they allowed a trial to overlap the real images and the painted ones in an attempt to catch a better glimpse of the paintings. The Hongjecheon River flowing to the Han River through places such as, Seodaemungu, and Mapogu, has been busy with constructions to restore its ‘natural form’ like in Cheonggyecheon. In a drier season with less rain, the dry river creates quite an ugly scene because of occasional weeds here and there, rough gravel, and enormous concrete boards used as piers of the bridge. Despite the new facilities such as, bike and workout courses, the region has given its people indelible memories of being a city slum with large sewers, livestock and dirty garbage floating in the river during floods for the last several decades. This has led to the doubt of its role as a life-saving water source for hundreds of years.

Unfortunately, a new era has come to the life-saving water and it is an era of transforming it into a large sewer, and a dried river over which there are bridges and piers in all directions. Moreover, the slumping Gyeongui railroads stretching throughout the river area impart wild and rough qualities from the remnants of industrial revolution. Song takes notice of street trees not for a great view, but to show derelict scenes in the naked riverbed sparsely dotted with dried earth. Unlike Song’s paintings full of green color, the transitory or quickly fading plants are not rooted deep in the earth. A probable big flood would easily sweep away most plants, a colony of weedy ephemerals growing only between rainy seasons. Many of these topographical traits of the region create themselves as snapshots of how Mother Nature is being treated indifferently by human beings.

Mother Nature, in Song’s paintings, is devoid of depth and inherent qualities like one would find in common synthetic lawn grass. The hurriedly-planted street trees remind us of the Saemaeul Movement in the 1970s, and the plants are destined to be plowed up at every seasonal change. The kitchen gardens seemed to be made by green thumbs’ secretive efforts and the weeds manage to survive in cracked walls of riverbanks. Her idiosyncratic perception of nature has been fueled by a tit for tat between pictorially-depicted spaces and illusions. The artist’s foundations encompass banished lands in a city and canvases of paintings. Nature as simulacra, like a green-colored carpet covering a canvas, exudes queer yet irresistible beauty in spite of the allusion to displeasure and satire. If premeditated, unlike haphazard developments, this would help the utilization of this area as an environmental outlet for the city dwellers by stripping away emotional void and stuffiness.

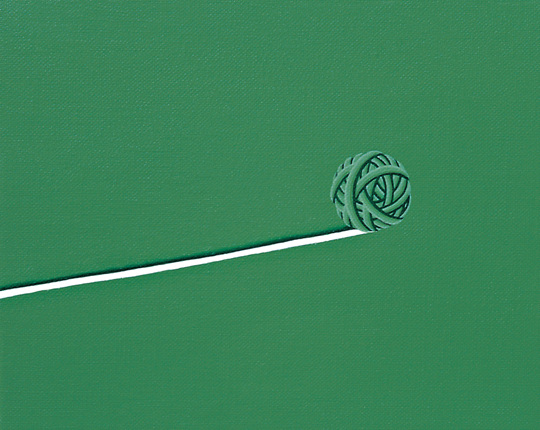

From the outset in the mid 2000, when Song dealt with nature as pseudo simulacra, her green color daubing canvases has played a crucial role. Only a few discernable paints belong to the contiguous colors of green. Barely-appearing red is the complementary color of green, and brown works to fade the green. White is used as a void or an empty space rather than a color, suggesting another plane by interacting with the natural and psychological color.

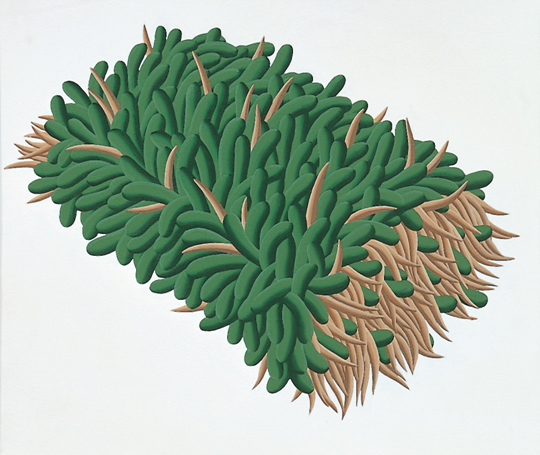

The artist stated that color names such as, opaque oxide of chromium, sound quite synthetic in contrast to the inherent richness and density. There were some works titled after the names of pigments in 2004 and 2005. Margarete Bruns pointed out in his theory of color that grasses do not exude a satisfying green, since the chlorophyll is usually accompanied by other elements. In order to sustain the strength and brightness of green, inorganic pigments are necessarily added into the vegetal pigments. It is the moment of transition from green of life to green of death. Bruns has also stated that this property of green color sometimes may lead to a green hell, as if creating a jungle strangling all living substances with its madness, and indiscreet growths.

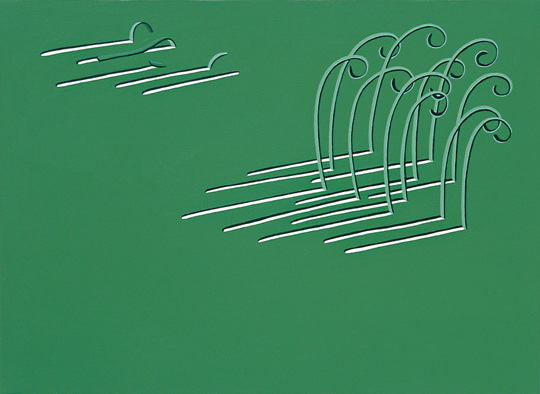

Bringing up an image of an existence that gives birth to its offspring and gobbles it up, green in Song’s works manifests ambivalence. It is often considered not only as the color of boredom and tackiness through the contemporary art’s divorce with representation, but also as the best color for resting and soothing the eyes. Located in the middle of the color spectrum, according to Goethe, it ‘resists advancements and is not able to advance.’ Nevertheless, the boring and receptive color wriggles in Song’s paintings. The green transforms itself into tentacled creatures or mineral resources full of potential energies. In Gardening (2006), the reddish sections of plants are correspondent of the varied green-colored stems through the uplifting contrast between complementary colors. The far ends of red and green seemingly cooperate by conjuring up the qualities of photosynthesis, changing the inorganic into the organic and creating an essence of life as in the quality of red blood.

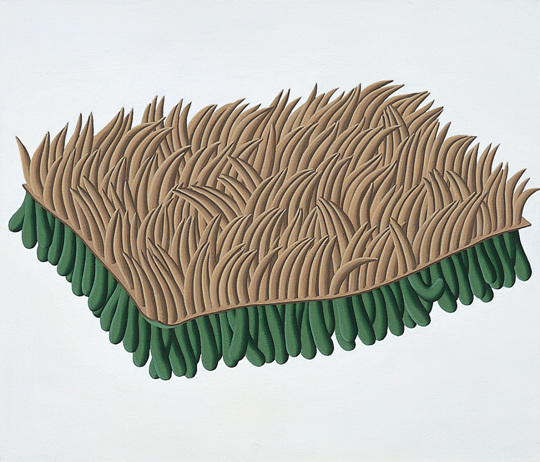

In one sense, Song’s paintings are no more than two-dimensional images daubed on canvas with green colors, which have traditionally been regarded as representative of Mother Nature. Graphical configurations and coloring strengthen the features of the existing two-dimensionality. The quick-drying acrylic colors provide a no-brushmarks finish and simply create clear images of colored planes without detailed descriptions. Some diluted illusions, however are cast upon the canvases with minimal reference points. The fleeting illusions take off inherently mysterious qualities of themselves. In short, there are two layers of illusions and two-dimensionalities. Another noticeable element of her work is the white space within. They are associated with a void and the dull traits found with the two-dimensionalities, revealing the naked quality of canvases. Moreover, the two-dimensionalities address the inherent synchronic structures within the paintings, namely temporal restraints. Moment-Pause (2001) of Song’s first exhibition presented an ambiguous memorial of landscapes by fixing a certain kind of circumstance into a specific moment, showing the artist’s visualization of self-consciousness.

As the evolutions into two-dimensionalities have already presented the correct courses through the art history, however, painters do not need to follow the trodden paths any more. According to Deleuze and Guattari, it is incorrect to identify the senses as sublimation of a purely two-dimensional visual. The alternatives suggested by Deleuze and Guattari, are not about turning (it) over, but about lifting up, collecting, accumulating, crossing over, raising and folding. Song amuses herself in the games of borders, without being involved with reductionism. Through a certain kind of role lead by green in the color spectrum, and the disclosure of an obverse side of mundane landscapes, the artist invites viewers to appreciate a clandestine pleasure through games, rather than to share some proven conclusions. That is the reason why Song’s paintings give attention to the relationship between details depicted in the landscape rather than to the landscape itself. The variations and expansions of details of a few simple landscapes are suggestive of the unique openness exceeding any existing framework.

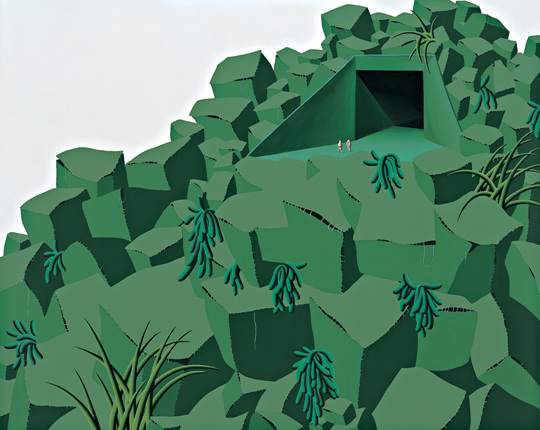

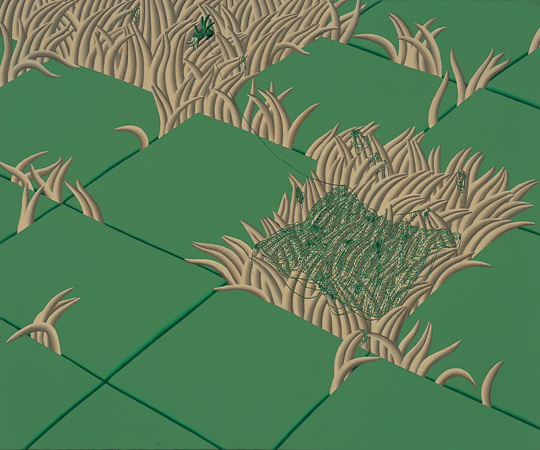

The square lawn panels as usual motifs, are arrayed on the empty white void as if they are sorts of grids. For instance, works of Two Fields (2005) or Whiz- (2003) make way for another plane of vision distinguished from the usual planes of vision, taking fixed viewers to another space over the grass fields. The simplified details and impressions of landscape collectively lead viewers to sense an infinite openness. It manifests uneasy anxieties as well as fantastic feelings as the white void reaches beyond the frame of the canvas. As the green panels, just like a basic unit of Mother Nature, seem to float in the air, it is a reckless attempt to divide the indivisible in the first time. Michel Serres stated in the Hermes series that bushes of realities are not accompanied with lattice. From the context, Song’s landscape resembles clouds. According to Michel Serres, a model of clouds is an aggregate, a nebulous set, a multiplicity whose exact definition escapes us, and whose local movements are beyond observation, being involved with an aspect of random dispersion, rather than with connections surrounding a certain static center.

Objects like crowds, and clouds are not drawn into the network composed of straight lines. Song’s fields run down into a void, suggesting white colored wastelands as a kind of maze. The openness with every possibility, and the space with directions determined only by coincidence, address both freedom and fear. A void is a characteristic of Chaos, as a disorderly space. What does Song’s strange Chaosmos, as organizations with precise measurements, underline in relations to contemporary paintings. Deleuze and Guattari stated in What Is Philosophy? that canvases are so immersed with the typical prescribed banalities that painters need to clear them off, press them into shorter thickness, or even deconstructed them into pieces. Through these series of elimination, we may inhale a breathe of fresh air blown from the Chaos leading us to a new vision.

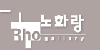

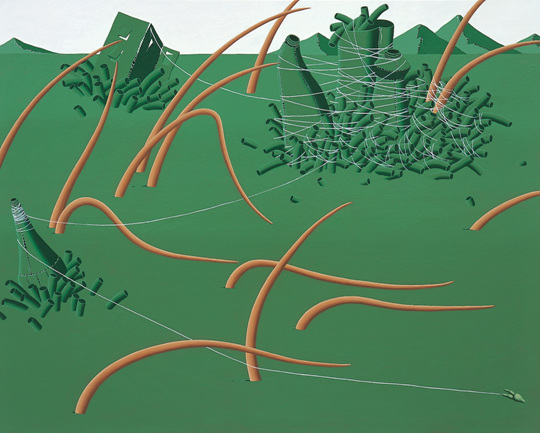

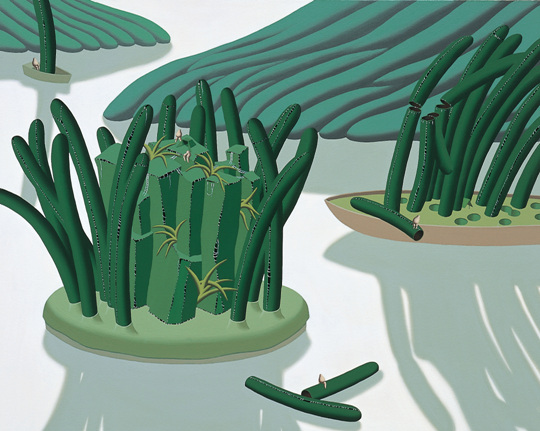

A narrative is an additive to Song’s experiments of visual languages in the works exhibited in 2007. The primary motifs such as tenements, buildings, characters and the like are added to the existing ones. As if composing imaginary kingdoms which are lacking the certainty of three-dimensionalities, the structures of bombproof gardens, and alters bring up images of roughly woven sets. Even when they are depicted like a city, the kingdom is still full of cacophonies. As deformed forms of fingers as terminal organs, the minimal characters allude to the retrogression or evolution of human beings. The finger humans represent present modern circumstances of objectifying or being objectified in every situation. The kennels flung onto the brown-turned grass and residential areas wrapped with threads indicate various aspects of barrenness. The entangled green planes, like a bombproof, create artificial mountains in Green shelter (2007). In Shelter from nature (2007), the finger humans hold the rituals for the sake of themselves in the pseudo sanctuary of nature.

A Builder series (2007) augments the barrenness through the abundant brown weeds, finger humans, and cocoon-shaped abodes seated around the large sewer and bridges. The delicate transformation of nature is not enough to hide the awkward sewing marks. Generally, the human finger functions as a tool of indications. Scientific techniques are representatives of relations among index concepts. Deleuze and Guattari stated that relations of indications in science give up infinity. Science is mainly involved with diagrams of index relations based on all kinds of limitations or borders. The synthetic environments surrounding the finger humans look like ideal mechanical systems with effective perfections. For example, Riverside (2007) shows a maze-like city where panoptical technologies are prevalent. As the feasibility is considerably unrealistic and feeble, it seems to float on fluid substances instead of being founded on solid ones. It is not coincidental that the white voids and the brown weeds take the forms of wavy oceans.

The orderly world in which the finger humans reside is none other than little islands floating on the sea of irregularities. What they presumed to be orders and reasons, and structures and organizations is at best a temporary composition seated upon the realities in disarray. Therefore, the spatial compositions with harmonized balances are still at risk. Song’s green territories are smudged with void holes, and segments getting nowhere and transformed into Chaos encompassing the realities. The controlling power of Chaos is maintained by measurements assimilating the territories to the geometric forms. Michel Serres also stated that the green territories address deviations from a lattice, as well as, the acute swerving from the parallel courses without any predetermined directions. It recognizes the existence of another space where all kinds of measurements disappear. The space brings up a number of potentially underlying spaces beneath the principle of oneness, with cracks, mazes and messes. A new mythology is being written in the space where the artist conjures up a new order, while jumbling up the geometry dominated by logos and interconnecting irrelevant factors.

Translated by Kang Young